Over the Imola race weekend, I noticed that some of the Formula 2 drivers were broadcasting their heart rates. Then I read that the FIA thinks it has to be careful with the data, which is absurd. A heart rate graph with a BPM reading means nothing.

Over the last 25 years, I’ve looked at thousands of hours of heart rate data as an endurance athlete and a coach. I thought that I’d detail when heart rate is informative and when it’s not.

Think of it like RPM for an engine. If an engine is running at 6,000 RPM, is it working hard? Impossible to tell, right? For a Corvette? Sure. For an F1 car? No. It depends on the redline of the engine.

Heart rate is like engine speed, and we’re all driving different cars.

Whenever you hear a comment like, “His heart rate was X!” you can smile and ignore it. Heart rate data is only meaningful when the readings are relevant to the individual through specific testing with the proper equipment. Otherwise, it’s just cocktail party chatter.

Here’s the checklist for meaningful heart rate data:

- Ignore formulas. Formulas like “220 minus your age” (for maximum heart rate) don’t work. Generic formulas describe populations, but rarely individuals. I’ve worked with athletes with maximum heart rates from 160 to 212. (The 212 was 45 years old.)

- Don’t trust estimates. Unless a person has spent thousands of hours comparing their perceived exertion to a proper reading, estimates are just guesses. And even with lots of experience, estimates are still questionable.

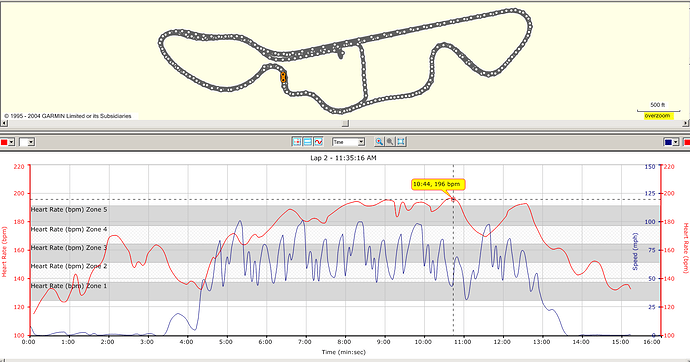

- Record electrical activity with a chest strap. Wrist-based, optical monitors attempt to read blood flow below the skin, not electrical activity of the heart. They’re an indirect measurement and horribly imprecise. Over long sampling periods—measured in hours—the average might be close, but their precision isn’t good enough to capture short-term variation. This is especially true when the device is being jostled around like running downhill or in high-vibration environments like karting.

- Find a personally relevant benchmark. There are three to choose from:

- Aerobic threshold (most important, but hardest to measure)

- Maximum heart rate (little use outside of cocktail parties)

- Anaerobic threshold (most practical to measure)

- When karting, discount for heat. For every 1˚C (1.8˚F) that body temperature increases, heart rate can increase 7-10 beats. At low intensities, 10 beats is not a big deal, but near anaerobic threshold, it is. So heart rate while karting on hot summer days will bias the reading upward.

- Compare readings to your benchmark as a percentage. This is the only way that heart rate readings can be compared to other people. “Joe’s at 160!” doesn’t mean anything. But “Joe’s at 102% of anaerobic threshold!” does. (Formula below.)

Or, if the above is too much hassle, you can go by feel, save money by not buying trendy gadgets, and ignore all the chatter.

How to find your anaerobic threshold

There is a huge amount of variation in our own thresholds. I’ve worked with athletes with anaerobic thresholds ranging from 150 to 195. And just like RPM, higher BPM values do not reflect higher performance, just unique physiology.

The most practical way to find your anaerobic threshold is Joe Friel’s 30-minute test. Again, you need to use a chest strap and a proper monitor. The effort should be self-propelled—no treadmills—and using a movement pattern that is well-trained. Runners should not use cycling and vice versa. If neither running or cycling is familiar, then try walking uphill. (For most people, a gradual hill of 1,000 vertical feet—or a 10-storey building—will be more than enough.)

How to find how hard you’re working

In a 20-minute race, if Joe has an average heart rate of 132 and John has an average of 157, who’s working harder? With just the BPM readings, it’s impossible to tell.

But if Joe and John had chest straps and knew their anaerobic thresholds (from above), they could measure the intensity of any workout with this formula:

[average of the workout] / [anaerobic threshold] x 100 = [percentage of anaerobic threshold]

(Most training watches have percentage of anaerobic threshold built in. Trendy gadgets rarely do…)

| Joe | John | |

|---|---|---|

| 20-minute average (BPM) | 132 | 157 |

| Anaerobic threshold (BPM) | 154 | 193 |

| Percentage of AnT (%) | 85.7 | 81.3 |

Joe, at 132 BPM, is working at 85.7% of his anaerobic threshold while John, 25 beats higher, is working at 81.3%. Although John’s heart rate is higher, his stress level is lower. But Joe, even with his lower heart rate, is working harder.

And heart rates in F1?

If the FIA ever starts broadcasting each driver’s percentage of anaerobic threshold, that would be very interesting indeed. But it would make for bad TV. I suspect the readings will be lower than the broadcasters want.

And the last thing TV needs is precision and relevance. So BPM-only readings will do nicely. The general public is none the wiser, the FIA doesn’t have to worry about “being careful,” and the teams don’t have to worry about creating any competitive disadvantages.

P.S. In 2018, I tested a Whoop against a proper heart rate monitor. I returned the Whoop for a refund.

P.P.S. If anyone goes through this process and records some karting sessions (with a chest strap), I would love to see the data.